Shredding outdated fundraising appeals is the simplest option for overworked fundraisers. Who’s got the time to catalogue them, archive them and save them for posterity. But, as Marina Jones and Jayne Lacny point out, not only did conducting these appeals fill us with joy, they provided a lot of learning – learning that has a place in informing future generations of fundraisers.

Scenario: You have fundraiser leaflets from a campaign you led five years ago, pre-pandemic. What do you do with them? Rip them up? Recycle? Archive them?

As you stand hesitantly in the middle of the office, slightly perspiring, paperwork in hand, what are your options? Throw them swiftly in the rubbish and go for a much-needed coffee? Head for the insatiable paper shredder? Put them in the recycling bin? You pause for a moment to think about their importance.

Then you have a wonderful Marie Kondo moment and realise that these documents fill you with joy. They bring back special memories. You simply can’t bear to destroy them. After all, they retell the history of a successful fundraising campaign of which you are hugely proud. The paperwork also shows the huge learning curve of fundraising staff, and the charity itself, as the campaign progressed. You sigh. The coffee can wait – you need to save these important records.

When does something become history?

The grim reality in the charity sector today is that many fundraisers facing the above scenario might well have destroyed the paperwork without considering them ‘historic’ or important. Not through malice or negligence or indifference. Operational matters naturally take precedence. The Charity Archives in the 21st Century report tells us that the state of charity archives is “on poverty row”. It states the situation is “far from good or even stable” as often charities don’t have the time, money or resources to save their records.

During the pandemic we were acutely aware that we were living through an historic era; that what was happening was (trigger warning – dreaded word) ‘unprecedented’. Yet during those times, the speed at which we had to react – to furlough, to continue to fundraise, to steward and engage – was dominated by the crisis. The usual processes weren’t there, and so the sector stepped up to adapt accordingly. However, what should the usual processes be when it comes to recording our fundraising history? When does something become history and why? Is a campaign from five or two years ago history? Is the Christmas appeal from five months ago? This week’s newsletter?

“Fundraisers are not always good at looking at our history. Too often our history depends on the longest serving member of staff in the fundraising team, or a volunteer, or vague feelings about ‘what works’ in our cause areas.”

Some might contend that history starts one second after the present and that primary sources – those telling a first-hand account – should be at the top of the list to be saved. After all, they offer detail and thought about the time or event and were created by people who were present. It must be said too that the pandemic – when we all took to working online – shone a light about not overlooking the importance of saving digital records.

Does your charity even have an archive?

Whose responsibility is it to ensure that our cultural and political memory is maintained? And if you have an archive, where is it stored and who decides what should be in it?

Some charities have the luxury of an archivist or an appointed member of staff to nurse and nurture records. Others are not so lucky. Many charities undoubtedly struggle. There are the boxes of old documents under the desk, so many that you can’t squeeze your legs under. There are the artefacts abandoned in the CEO’s garage. There are filling cabinets heaving with a mishmash of uncatalogued documents. There are those records neglected in cold and damp cupboards or placed next to air conditioning systems. Worst still, are the empty spaces where papers used to be.

Even those charities that have taken steps to honour their past can hit problems, and we have heard of one major charity that has let go of its archivist in the past year. The reality is that charities work on a shoestring budget. Also, if an archive exists, it may focus only on one area – business records, board reports or financial accounts. Few have the luxury of a paid archivist or specialist skills.

Of course, SOFII is an incredible resource for capturing the history of campaigns and this article about Guard Books is worthy of exploration. In it, Ken Burnett talks of the “forensic trail” that such documents provide that otherwise would have been lost. But how many of us are doing that? And don’t we need something more formal?

“Fundraising can be the invisible piece within the philanthropic landscape and without finding a way to share, to celebrate and tell our stories, they get lost.”

Marina has a drawer in a desk at her home with her favourite examples of campaigns she has worked on. She has the photo roll on her phone which captures parts of it – the donor dinner, the fun and personal thank you. Jayne has kept all the documentation – mostly digital – from an emergency website appeal she ran for a dementia charity when we first went into lockdown in March 2020.

However, we are not sure that we as fundraisers are always good at looking at our history. Too often our history depends on the longest serving member of staff in the fundraising team, or a volunteer, or vague feelings about ‘what works’ in our cause areas. Without the longer history, what are we missing? And what do we learn from valuing our past?

By looking at an archive of our fundraising, we learn what has been tried and tested (and hopefully what worked and what didn’t work). Hopefully we connect again to the why and how we want to change the world – maybe we even see how much progress has been made to solve an issue. Nostalgia can be a useful tool in our fundraising (and not just on legacy fundraising) in order to connect our audiences and supporters with why they first made a gift, along with their giving identity with us, and the charity. Too often there can be a dismissive ‘we tried that 10 years ago (20 years ago) and it didn’t work, so we won’t do it again’. Or the opposite, ‘we have been doing this since 1989 and it is our biggest campaign we cannot change it’.

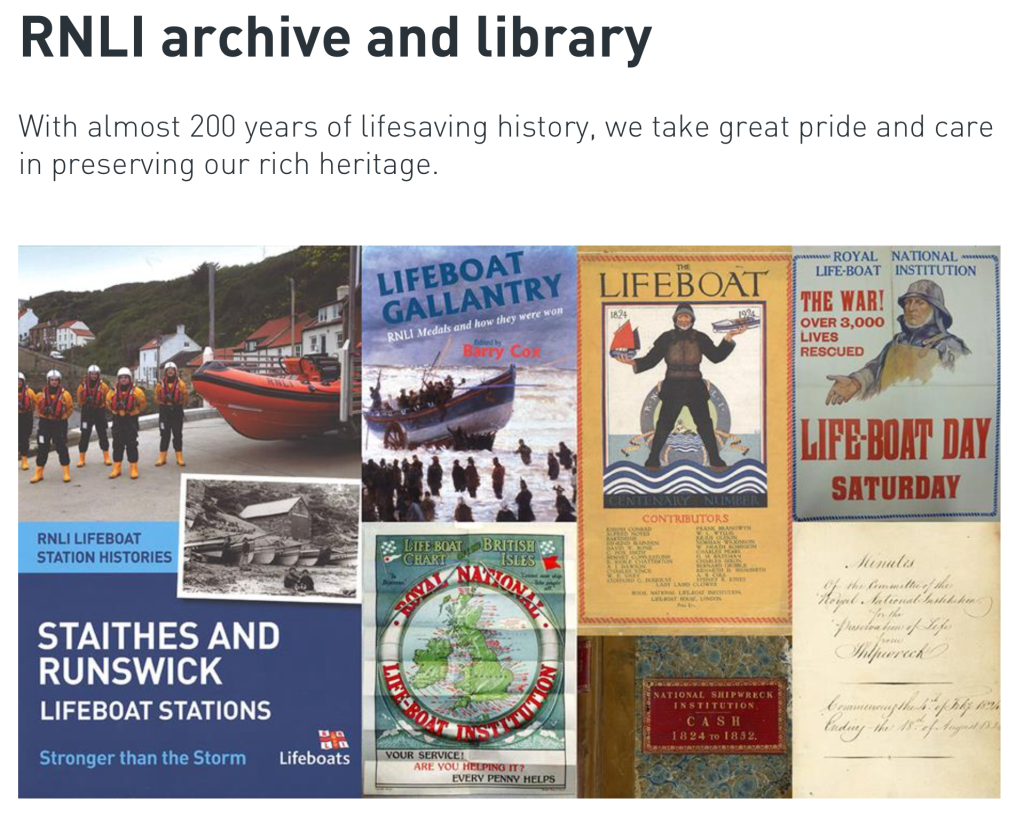

The archives that exist are dominated by a sprinkling of major charities, foundations and some prominent individuals, and they tend to be about philanthropy not fundraising. Some charities have archives, for example, the Salvation Army (where fundraising is stored under public relations), or Oxfam (at Oxford University), Barnardo’s and RNLI. But is it fundraising that is actually and actively archived; or does it only happen by accident?

How would an archive of the history of fundraising work?

All good archives have a collecting policy that details what they will and will not collect, and why they will or will not collect them, to ensure that what they do keep is useful and appropriate; the archivist brings the skill of knowing what to keep and what to leave out.

Fundraising can be intangible and happen in the moments, in the relationships, in the making the ask, in the pause after the request for support, in the thank you card, etc. So a fundraising archive will need a specialist fundraising archivists who understands this and can reflect it in the policy.

Further, many archives restrict access during the lifetime of people mentioned and with GDPR legislation in the UK and Europe, what could be included (or not) would need to be thought about carefully. After all, do we need to know what size shoes the donor takes for the hard hat/steel capped tour of the capital building site?

Naturally, we can look across The Pond and envy the facilities of The Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC. Although its founding donor – the British chemist, James Smithson, (5 June, 1765 – 27 June, 1829) – never stepped foot in the US, his legacy provided a glorious home for the charitable sector, among many other things. He gave around US$9m (£7.1m) in today’s money to create it. Imagine if he had done so in this country! He was a student at Pembroke College, Oxford and just inside the first quad, you can find this plaque to his memory.

Jayne advises charities and grant-giving trusts and foundations about where to place their archives externally, but is often met with a dearth of places that would accept such documents. There is no one designated location solely for charity archives in the UK, although the UK Philanthropy Archive at the University of Kent, which opened in 2019, was established to collect, preserve and provide access to archives relating to philanthropy in the UK. They collect the archives and papers of UK philanthropists, philanthropic trusts and foundations, philanthropic networks, etc.

“The archives that exist are dominated by a sprinkling of major charities, foundations and some prominent individuals and they tend to be about philanthropy not fundraising.”

A dream scenario would be to see the creation of an archive solely for charities in this country, where fundraising history takes pride of place. But where would such a fundraising archive begin?

If an open-source archive were created, what might it look like? What would its collecting policy be? Would it have all the emails and notes on a campaign, the various drafts, the final appeal, the letters in response, the thank you letter and the internal post campaign report? Careful curation would be needed to decide what to throw and what is vital to keep. We need to actively engage in what is kept of our history – not to be nagged by a volunteer to keep two copies of every annual report. How can we help the fundraisers of the future to know what worked, what didn’t, and inspire them to greater things, if we don’t archive these things?

The lived experience of our beneficiaries help us shape the delivery of our work, and how we represent and co-create work – how could we apply that to how we record our fundraising history?

We need to think about how we want our stories to be told. Fundraising can be the invisible piece within the philanthropic landscape and without finding a way to share, to celebrate and tell our stories, they get lost. History so the saying goes gets written by the victors – and fundraisers have been bashful or ignored in the telling of what their contribution achieves and therefore our own history is being sidelined.

Back to the example appeal of the pre-pandemic appeal with which we introduced this blog. What did you do with your fundraising materials from that time? If you put them in the recycling, do you wish you hadn’t? And if you do regret it, what are you going to do now to make sure current and future appeals are spared that fate and are available for your successors to learn from?

Marina Jones is Deputy Development Director at English National Opera and leader of Rogare’s fundraising history/historiography project. You can read Marina’s blog about fundraising history here.

Jayne Lacny researches and writes about the charity sector as well as advising charities, grant-giving trusts and major donors about how to safely care for their archives through her Notes on Philanthropy consultancy. She is also a member of the Rogare history project team.