In the third and final part of his exploration of the attacks on fundraising, Ian MacQuillin argues that the ideological narrative the profession needs to defend itself is undermined by anti-fundraising attitudes in its midst.

In Part 1 of this blog, I made the case that the repeated recent attacks on charities by the state and media – particularly attacks on fundraising – were ideological in nature. Then in Part 2 I argued that this was rooted in something that I called ‘Voluntarism’, which requires charity to be done out of self-sacrificial, voluntaristic motives and not to be too ‘professional’.

I also briefly outlined the counter ideology of Professionalism – the one I hope most in the voluntary sector subscribe to.

With the sector striving for a ‘new narrative’ to counter negative publicity and media hostility, one option is simply to roll out Professionalism as a counter ideology. Yet before that can happen, we have to accept that we are under ideological attack in the first place.

Ideological arguments have a different form to other forms of thinking and anyone adopting an ideological argument is unlikely to be swayed by non-ideological counter arguments: political philosophy rarely knocks back political ideology on a public stage.

So for instance, when people adopt an ideological opposition to, say, six-figure charity salaries, there is little point trying to use rational explanation to change their minds – perhaps by pointing out how every pound spent on the ceo’s salary delivers x more pounds’ worth of benefits to service users. This is because the ideological position that charities ought not pay six-figure salaries is not contingent on the efficacy of the staff in receipt of those salaries.

Instead, we need to use different ideological rhetoric that makes its own case rather than attempts to refute the anti-salary argument premiss-by-premiss. That might look like this:

- Voluntarist argument: It’s totally unethical for charities to waste donors’ money on fat cat salaries when that money should be going on improving peoples’ lives.

- Anti-Voluntarist rebuttal: We need to pay competitive salaries to ensure that we attract the right staff to deliver the services we need to improve the lives of our beneficiaries. Sometimes that means paying very high salaries, but you have to remember that those salaries will result in better outcomes for our beneficiaries.

- Professionalist counter-argument: We’re here to make the world a better place and we’re going to do what we need to do to make that happen for the sake of the people who rely on us. If we need to pay a certain salary to get a certain person to do a certain job to make the lives of our beneficiaries better – then that’s what we’ll do.

The Voluntarist argument alleges that it is unethical to pay charity staff high salaries because that money is diverted from improving peoples’ lives.

The anti-Voluntarist rebuttal tries to respond to each of those points, but in doing so comes across as special pleading, as one almost always does when one is forced into declaring: ‘No, I’m not unethical, honestly!’ Any rebuttal is inevitably shaped and structured by the argument it is attempting to confront.

The Professionalist counter-argument simply ignores the allegations of unethical practice and states its own case about why charities pay appropriate salaries for appropriate staff. It doesn’t respond to the Voluntarist argument at all – because it is its own ideological argument. But implicit in this ideological statement is the notion that it isn’t at all ‘unethical’ to spend money on the salary of a person whose skill will make people’s lives better.

Here’s another, similar example (similar in fact to the one used by Michael Portillo recently on BBC Radio 4’s The Moral Maze):

- Voluntarist argument: Don’t you think donors would be aghast to find out that their £10 a month was going towards the ceo’s six-figure salary?

- Anti-Voluntarist rebuttal: Many charity ceos have incredibly complex jobs running multi-million pound, often international, organisations, and they get paid a lot less doing this than they would if they did similar jobs in the commercial sector.

- Professionalist counter-argument 1: That all depends on how good the ceo is.

- Professionalist counter-argument 2: That all depends on why donors are giving to a charity in the first place. Are they giving to change the world using any means necessary, in which case they probably won’t care how much is spent on the ceo’s salary providing she’s doing a fantastic job? Or are they giving with a fixed idea how the charity ought to operate – in which case they might well get upset if the charity doesn’t spend donations they way they think they ought to be spent? That, however, doesn’t mean they are right.

So Professionalism is a good candidate for the ‘new charity narrative’ that so many are currently seeking? What that narrative might look like beyond the scope of this blog, though I will come back to it.

Irrespective of the narrative we ultimately develop, we must acknowledge that the attacks on charities are ideological, and we don’t yet have any consistent, coherent ideological defence.

An anti-fundraising undercurrent

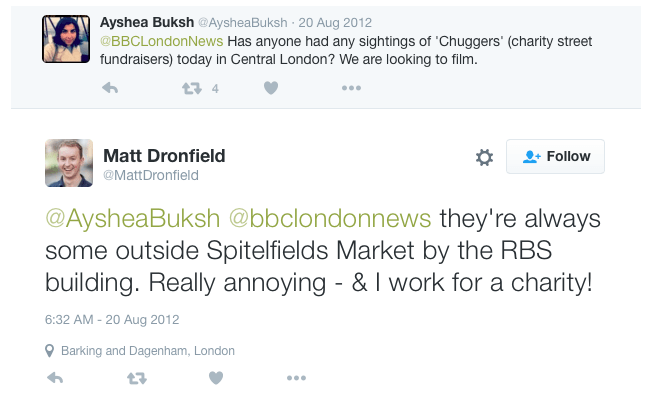

However, there is a problem with adopting Professionalism as our ideological narrative. That’s because many nonprofit professionals are actually Voluntarists, particularly when it comes to fundraising. In fact, many of the anti-professional fundraising components of Voluntarism – such as a distaste for mass market methods and corporate partnerships/sponsorships – are shared by people who would probably otherwise consider themselves to be Professionalists. We’ve all read Tweets that begin: ‘I work for a charity but I hate that we use chuggers.’ There’s no bigger illustration of this than the overriding attitude among many charity and nonprofit professionals that fundraisers are some kind of collective ‘necessary evil’.

This an ideological approach to fundraising that has allowed these Voluntarist attitudes to colonise Professionalism, weakening and undermining fundraising’s collective efforts to defend, champion and self-determine its own actions.

Sir Stuart Etherington’s review of fundraising last year is a Professionalist trope, yet it is riven with anti-fundraising Voluntarist doctrine. Take the so-called ‘right to be left alone’, which is one of the report’s core ideas. Sir Stuart maintains that people have a ‘right to be left alone’ and that fundraisers must therefore respect this right and balance it against their (fundraisers’) right to ask for support.

The claim that people have a ‘right to be left alone’ receives no theoretical support or justification. We’re not given any reason to suppose that such a right even exists, or from where it derives any authority. Do we have a right to be left alone from everyone (including individuals) or just organisations? If it’s only from charities, why don’t we have a similar right to be left alone from or other marketers (none of us has a ‘right to be left alone’ from Amazon, or the BBC, or the Green Party)? However, the right to be left alone from charities appears only to apply to fundraising asks and not other types of communications? Why does a member of the public have the right to be left alone from an ActionAid fundraiser but not an ActionAid campaigner?

“It beggars belief that NCVO, the organisation that champions charities’ independence from government in the policy and campaigning sphere, should be acting as the Cabinet Office’s enforcer in bringing fundraising to heel.”

These theoretical inconsistencies exist because the claim that the public have a ‘right to be left alone (from fundraisers, but nobody else)’ is an ideological one and not something that has been derived from philosophical analysis.

There are many other similar ideological attacks on fundraising that appear to run counter to the core tenets of Professionalism: a state-appointed fundraising regulator, a state-imposed service that will prevent charities executing their duty to ask for support, a code of practice that seems certain not be written by members of the fundraising profession (at the time of writing, it seems likely fundraisers will have minimal input into it). These are all ideological attacks on fundraising, and particularly the independence of fundraising. What seems staggering is that they have been or are being recommended, imposed, delivered or welcomed by people and organisations that we should expect to have rejected them out of hand.

“The claim that the public have a ‘right to be left alone (from fundraisers, but nobody else)’ is an ideological one and not something that has been derived from philosophical analysis.”

That NCVO, the organisation that champions charities’ independence from government in the policy and campaigning sphere, should be acting as the Cabinet Office’s enforcer in bringing fundraising to heel, truly beggars belief.

And many of us were bemused at the spate of press releases emanating from the Institute of Fundraising last year welcoming each new move by NCVO, the Office for Civil Society and others. The context for our bemusement was that the IoF kept ‘welcoming’ ideological encroachment into territory we assumed it was committed to ideologically defending.

Describing anti-fundraising ideological encroachment into the Professionalist Charity Ideology is not just a matter how we can combat negative publicity. It has very practical consequences: the Fundraising Preference Service is the result of ideologically-motivated state interference in the voluntary sector, against which the fundraising profession had no adequate ideological defence (the FPS has been euphemistically described as being “close to the minister’s heart” by Stephen Dunmore, the interim ceo of the Fundraising Regulator).

We are seeing further ideological impacts in the way that CC20 – guidance about fundraising for trustees – is currently being revised by the Charity Commission. Sir Stuart’s review has recommended that trustees take direct responsibility for the fundraising function, even down to writing marketing copy themselves. This is an idea (a patently ridiculous one!) that derives from the ideological notion that fundraisers are a ‘necessary evil’ and entirely to blame for what happened in British fundraising last year. It couldn’t be more Voluntarist and anti-Professionalist if it tried: it’s saying that volunteer trustees should take over copywriting fundraising materials because the professional fundraisers can’t be trusted to do it.

The Charity Commission has responded to the ideological demand that trustees take control of fundraising (it’s already a legal duty that they take ‘responsibility’ for fundraising; now they are being urged to take ‘control’ of it – a different thing) by revising its CC20 guidance for trustees.

The existing CC20 is an excellent document that provides all the information trustees need to make the best-informed decisions about fundraising – it’s not the fault of the guidance that trustees were not following it. The revision shifts the focus from what they need to know, to what they need to do, with the addition of six new ‘principles’. This is in response to an ideological recommendation that trustees become more active in surpervising fundraising. But in doing so, the Charity Commission has removed huge chuck of detail and information that trustees need to properly execute their duties vis-à-vis fundraising.

I’m not saying that the Charity Commission is staffed by ideologues or that the revision of CC20 is ideologically driven by Voluntarist attitudes held at the commission. But it is a response to circumstances that are ideological and is inevitable shaped by those ideological circumstances.

Conclusion: the importance of an ideological perspective

There are four conclusions we must take from this three-part blog.

1 The attacks on charity and fundraising are ideological

There exists an ideology that views charity in a particular way and is the fount of the opposition, criticism and hostility when charity is not conducted that way. This Voluntarist/anti-Professionalist ideology is coherent and consistent. I’m making no claims about whether its deployment in the media is co-ordinated.

The point of identifying as ideological the attacks on charity (generally) and fundraising (specifically) is not to dismiss them out of hand as dogma, doctrine, rhetoric or bad philosophy. It is to understand them for what they are: part of a system of political thought, with a recurring pattern, that is held by significant groups, that advances an agenda for controlling public policy about how the voluntary sector should operate, and justifying changes to existing social and political arrangements to further the advance of this agenda.

By identifying the attacks as ideological in nature, we can construct the appropriate response to those attacks, which we have so far failed to do. This leads to the second conclusion.

2 We need a counter ideology

The charity sector is looking for a ‘narrative’ with which to defend itself against political, media and public hostility. To counteract ideological attacks, we need a counter-ideology of our own. The most promising counter-ideology is Professionalism, and I’ve outlined some ideas about how this could be used above.

3 There is an anti-fundraising undercurrent

Unfortunately, Professionalism is seriously undermined by the anti-fundraising sentiments it contains, the most virulent of which is that fundraisers are a ‘necessary evil’.

4 Fundraising cannot be sacrificed

And so to the fourth conclusion – the first task in developing a new ideological narrative that will support charities and fundraising is to reverse the flow of these anti-fundraising streams within Professionalism. As we said in our recently-concluded review of relationship fundraising, the onus to build good working relationships with colleagues, peers and boards – in order to dispel the ‘necessary evil’ notion – has to come from fundraisers, since it doesn’t seem likely the impetus will come from anyone else.

In defending the third sector against all ideological attacks, we need to be unashamed Professionalists. But we can’t do that unless we are also prepared to extend the same ideological claim of professionalism to fundraising.

Fundraising is an inherent and integral part of the Professionalist Charity Ideology and it cannot – must not – be sacrificed to the Voluntarist agenda, either to protect other tenets of Professionalism or because some Professionalists hold a naïve conception of fundraising as a ‘necessary’ evil.

If professional fundraising falls, the rest of professional charity won’t be far behind.

- Ian MacQuillin is director of Rogare – The Fundraising Think Tank

One thought on “NEW IDEAS: The ideological attack on fundraising, Part 3 – Why we need an ideological defence”